The alarm clock stands as an almost indispensable fixture in contemporary life, a ubiquitous tool orchestrating adherence to the structured cadences of modern schedules. Yet, for millions, its daily call is not a gentle beckoning but an unwelcome intrusion, often transforming the transition from sleep to wakefulness into a period of displeasure and acute stress.

This report will critically examine the complex, and frequently detrimental, relationship between the sound design of alarm clocks and human psycho-physiological responses upon waking. It will trace the evolutionary trajectory of alarm technology from rudimentary ancient devices to sophisticated modern systems, explore the cultural and behavioral paradigms that shape their use, analyze the profound impact of various sound characteristics on morning stress levels and cognitive function, and evaluate emerging innovations in waking technology that aspire to foster a less jarring and more harmonious awakening experience.

The central thesis posits that a historical emphasis on mere functional efficacy in waking, coupled with technological and economic expediencies, has largely overshadowed considerations of user well-being, leading to a legacy of alarm sounds that can act as significant morning stressors. By dissecting the psychological, physiological, historical, and socio-cultural dimensions of this everyday interaction, this report aims to illuminate pathways towards redesigning the morning ritual, moving from panic-inducing alerts to peace-promoting awakenings.

The routine act of being awakened by an alarm clock, particularly by the abrupt and often harsh sounds characteristic of many devices, can exact a significant psychological and physiological toll. This section dissects the immediate and short-term consequences, focusing on the body's innate stress mechanisms, subsequent cognitive impairments, the nuances of auditory processing during sleep, the emotional ramifications, and even extreme perceptual phenomena that shed light on the intensity of auditory experiences during sleep-wake transitions.

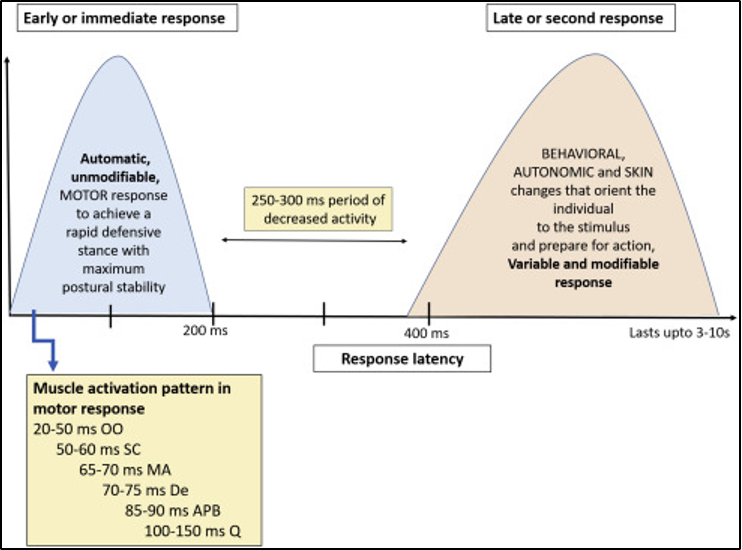

The sudden, loud intrusion of an alarm sound into the quiet of sleep often acts as an acute stressor, initiating a cascade of physiological responses mediated by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This activation is akin to the "fight-or-flight" response, an ancient survival mechanism designed to prepare the body for immediate action in the face of perceived danger.1 The brain, especially when roused from deeper sleep stages where higher-order cognitive processing is diminished3, may interpret the alarm's acoustic characteristics—its loudness, abrupt onset, and often non-naturalistic timbre—as a generic "threat signal." This interpretation bypasses nuanced cognitive appraisal and directly activates primal threat-detection circuits. Consequently, the body is rapidly shifted from a state of rest to one of high alert.

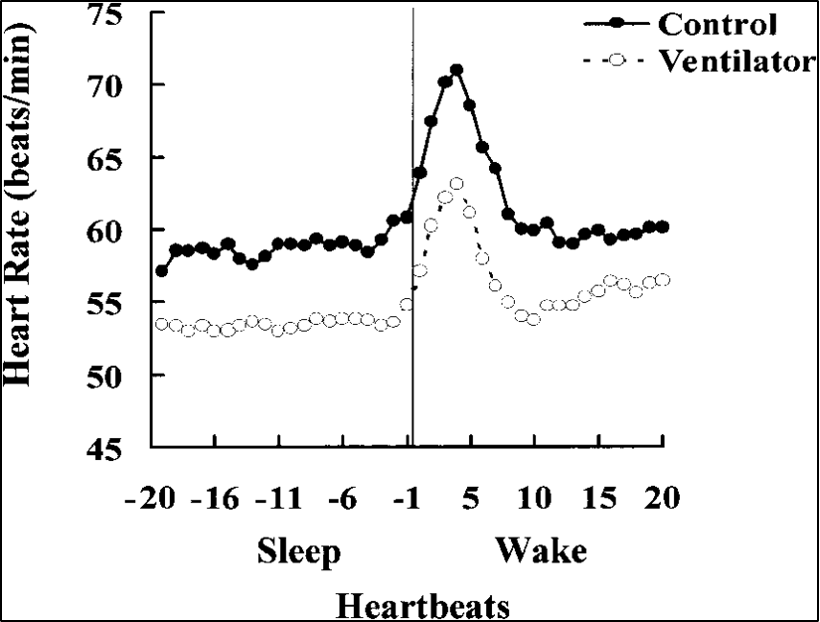

This physiological upheaval manifests in several measurable ways. Cardiovascularly, alarm-induced waking is consistently associated with an increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure. Studies have documented higher waking heart rates on alarm days compared to days with spontaneous awakening (e.g., a mean of 61.5 beats per minute versus 58.75 bpm).2 Emergency alarms, which are typically designed to be maximally arresting, elicit even more pronounced increases in heart rate, with reactivity (the difference between baseline and peak heart rate) measuring between 38 - 56 bpm.6 Similarly, abrupt awakenings can cause significant surges in morning blood pressure.1 Such daily cardiovascular strain, particularly if repeated over years, could contribute to cumulative stress on the cardiovascular system, posing a concern for individuals with pre-existing vulnerabilities.2

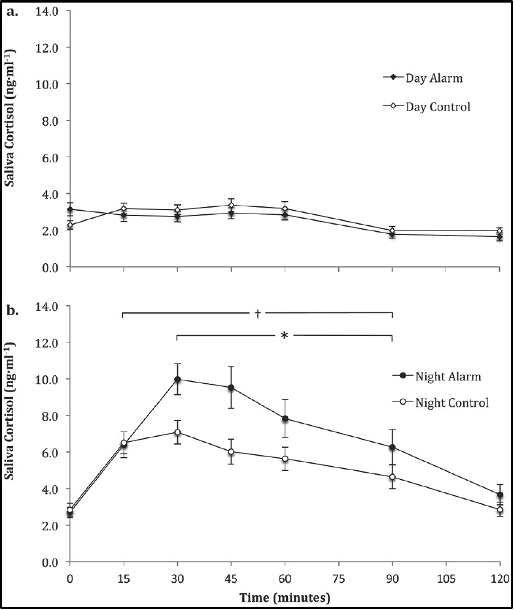

Hormonally, these sudden awakenings trigger the release of stress hormones, notably adrenaline and cortisol. Alarm sounds can precipitate an immediate adrenaline rush.1 The impact on cortisol, a primary stress hormone, is particularly significant. While a natural rise in cortisol in the morning (the Cortisol Awakening Response, or CAR) is a normal part of the body's preparation for wakefulness 8, alarms can cause an exaggerated or mistimed spike. Research indicates that alarms, especially those occurring at night, can evoke a significant hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response, leading to higher cortisol levels compared to daytime alarms or natural waking.6 Even non-emergency alarms have been shown to elevate cortisol.2 This hormonal surge underscores the body's perception of the alarm as a stressor.

The intensity of this physiological response can be further modulated by the sleep stage from which an individual is awakened. Being roused from deep sleep (N3, or slow-wave sleep) or Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, stages where the body is least prepared for sudden arousal and arousal thresholds are highest, can exacerbate the shock and the subsequent stress response.1 During N3 sleep, for instance, some individuals may require sounds louder than 100 decibels to awaken.11 The abrupt interruption of these restorative sleep stages by a loud alarm forces a more jarring transition to wakefulness, amplifying the physiological stress.

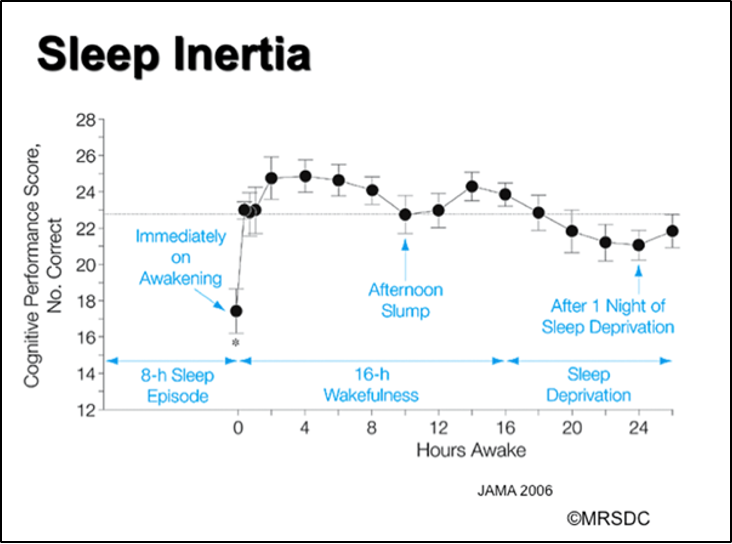

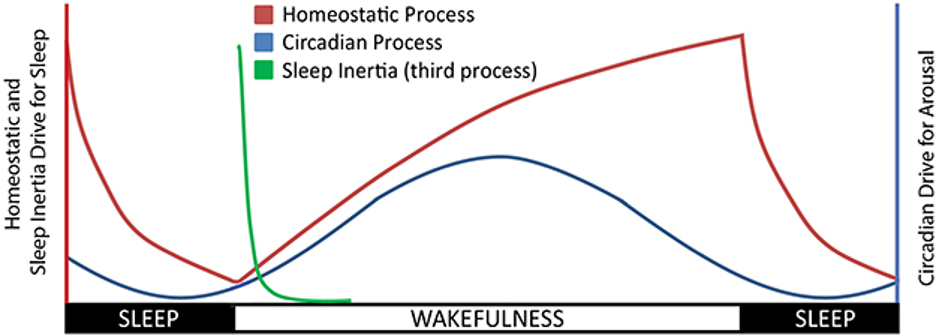

Beyond the immediate stress response, waking to an alarm often precipitates a period of cognitive impairment known as sleep inertia. This transitional state is characterized by grogginess, reduced alertness, disorientation, and demonstrable deficits in cognitive functions such as reaction time, short-term memory, and decision-making capabilities.1 The duration of sleep inertia can vary from a few minutes to, in some cases, up to four hours, significantly impacting an individual's readiness for the day.7

Abrupt awakenings induced by alarm clocks, particularly from deep N3 sleep or REM sleep, are known to significantly worsen the severity and duration of sleep inertia.1 For example, studies have shown that alarm-induced waking leads to slower reaction times compared to spontaneous waking (e.g., a mean of 0.372 seconds versus 0.315 seconds).2

Waking directly from deep sleep can impair cognitive abilities, including short-term memory and even simple counting skills, for as long as two hours post-awakening.1 These cognitive deficits have practical implications for any tasks requiring immediate mental acuity upon waking, such as driving, operating machinery, or making critical judgments.16 The neurochemical basis of sleep inertia is thought to involve the lingering presence of sleep-promoting neurochemicals in the brain and the time it takes for wakefulness-promoting neural systems to achieve full activation.14

The experience of severe sleep inertia, often a direct consequence of being startled awake by a jarring alarm, can paradoxically reinforce reliance on these very types of alarms. Individuals who feel intensely groggy and struggle to become fully awake may develop a belief that they "need" an extremely potent, disruptive stimulus to rouse them. This can lead to a cycle where they continue to use, or even seek out, louder or more grating alarm sounds, or resort to setting multiple alarms in succession.17 This behavior stems from a fear of not waking up otherwise. However, such strategies only perpetuate the problem: repeated exposure to harsh awakenings further exacerbates sleep inertia and the associated physiological stress, making a natural or gentle awakening feel insufficient.

Such a pattern is also intertwined with psychological habituation, where the brain begins to "tune out" familiar alarm sounds, potentially prompting users to escalate the intensity of the stimulus to ensure they wake up 14, thereby creating a vicious cycle of disruptive awakenings and persistent morning grogginess.

During sleep, the brain is not entirely disconnected from the external sensory world. While the arousal threshold—the intensity of a stimulus required to cause awakening—is significantly increased compared to wakefulness, this sensory disconnection is partial and reversible.19 The sleeping brain continues to process auditory stimuli, albeit differently than when awake. Neuroimaging studies have shown that auditory stimuli presented during sleep elicit activation in primary auditory processing regions such as the auditory cortex, thalamus, and caudate nucleus, during both wakefulness and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.4 This indicates that the fundamental machinery for hearing remains operational.

However, higher-order brain regions responsible for more complex processing and conscious perception, including areas in the left parietal lobe, prefrontal cortex, and cingulate cortices, exhibit less activation during NREM sleep compared to wakefulness.4 This reduction in activity in associative cortices suggests a diminished capacity for detailed interpretation, contextualization, and conscious awareness of the sounds being processed.

Furthermore, the neural feedback from higher brain centers that, during wakefulness, helps in understanding sound and anticipating subsequent auditory events—a process reflected in the attenuation of alpha-beta brain waves—is largely absent during sleep.3 This lack of "top-down" cognitive modulation might contribute to why alarm sounds are often perceived as raw, unfiltered, and intensely startling stimuli.

Interestingly, the sleeping brain appears to retain a capacity to differentiate sounds based on their emotional or survival relevance. Studies have found that the left amygdala and left prefrontal cortex—regions critically involved in emotional processing, particularly threat detection—are more activated by effectively significant stimuli (e.g., meaningful or personally relevant sounds) than by neutral stimuli, even during NREM sleep.4 This suggests a primitive level of "meaning-making" or salience detection persists, allowing the brain to prioritize potentially important environmental cues.

The stage of sleep also profoundly influences arousal thresholds and the nature of awakening. N1 sleep, the lightest stage, is the easiest from which to awaken.10 As sleep deepens into N2, characterized by sleep spindles and K-complexes, arousal becomes more difficult.11 N3 sleep, or slow-wave sleep, represents the deepest stage of NREM sleep and has the highest arousal threshold; loud noises, sometimes exceeding 100 decibels, may be required to awaken an individual.11 Awakening from N3 sleep is strongly associated with significant sleep inertia.10 During REM sleep, although brain activity resembles wakefulness and dreaming occurs, individuals can also be difficult to rouse. Neurochemically, levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in arousal, are lowest during NREM sleep and highest during wakefulness and REM sleep.

This interplay between ongoing auditory processing and diminished higher-order cognitive interpretation during sleep creates a paradox.

While the brain can detect effectively significant sounds, the absence of robust top-down attentional feedback means that an alarm sound—even if "neutral" in its intended meaning but acoustically jarring due to its high intensity, rapid onset, or harsh timbre—might be processed with high salience by primitive auditory pathways and the amygdala.

Without the moderating influence of cognitive interpretation that occurs during wakefulness (e.g., recognizing "this is just my alarm, it's not a real threat"), the salient acoustic features may disproportionately activate subcortical and limbic areas associated with alarm and stress. This could lead to a strong physiological and emotional reaction that is not "dampened" by rational thought, making the experience more akin to a genuine emergency signal. This is further compounded by the typical lack of a "prepulse" – a gentle preceding stimulus that can reduce the startle response, as seen in prepulse inhibition phenomena 21 – in most alarm clock designs, thereby maximizing the startle effect.

The physiological stress and cognitive disruption caused by alarm clocks are often accompanied by a range of negative emotional responses. Waking to an alarm is frequently associated with feelings of annoyance, tiredness, and even states resembling depression or nervousness.17 Specifically, the use of loud alarm sounds has been directly linked to increased feelings of annoyance upon waking.

For some individuals, the negative experience is not limited to the moment of awakening; anticipatory anxiety or a sense of dread can develop concerning the alarm sound itself.13 This can be understood as a conditioned response, where the alarm sound, through repeated association with the unpleasant jolt of being startled from sleep and the subsequent stress of beginning daily obligations, becomes a trigger for negative emotions even before it sounds.

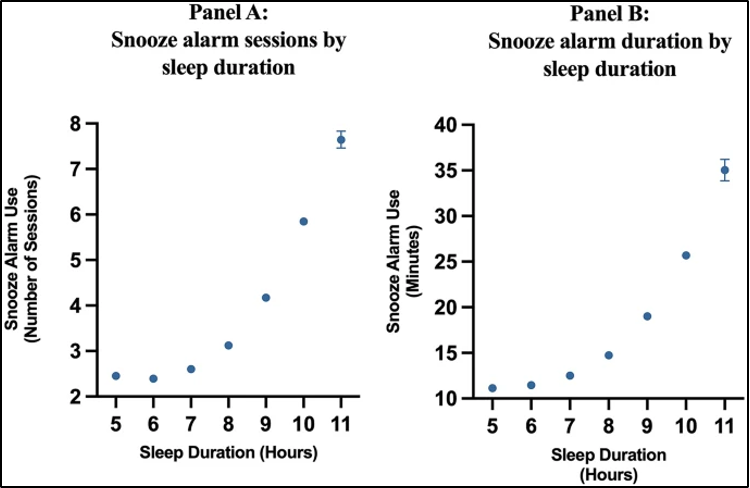

The nature of the alarm sound plays a crucial role in setting the emotional tone for the morning. Loud, sudden, and harsh sounds are more likely to induce stress and negatively impact overall mood, contributing to what some have termed the "alarm clock blues".1 Data from studies analyzing alarm usage logs show that individuals who use alarms more frequently throughout the morning (indicative of hitting snooze multiple times) or those who use loud alarms tend to report higher levels of annoyance.17

This repeated pairing of an unpleasant stimulus (the jarring sound) with an unpleasant experience (abrupt, stressful awakening) can lead to a conditioned aversion. The alarm clock, rather than being perceived as a neutral, helpful tool, can become symbolic of this daily negative encounter. Over time, the user's relationship with their alarm can transform from a purely functional one to an antagonistic one, where the device itself is viewed as an adversary. This pre-existing negative mindset, a form of conditioned negativity towards the alarm, can then amplify the actual stress and displeasure experienced upon waking, as the individual is already primed for an unpleasant interaction. The alarm, therefore, doesn't just signal the start of the day's demands but can become an independent source of morning stress.

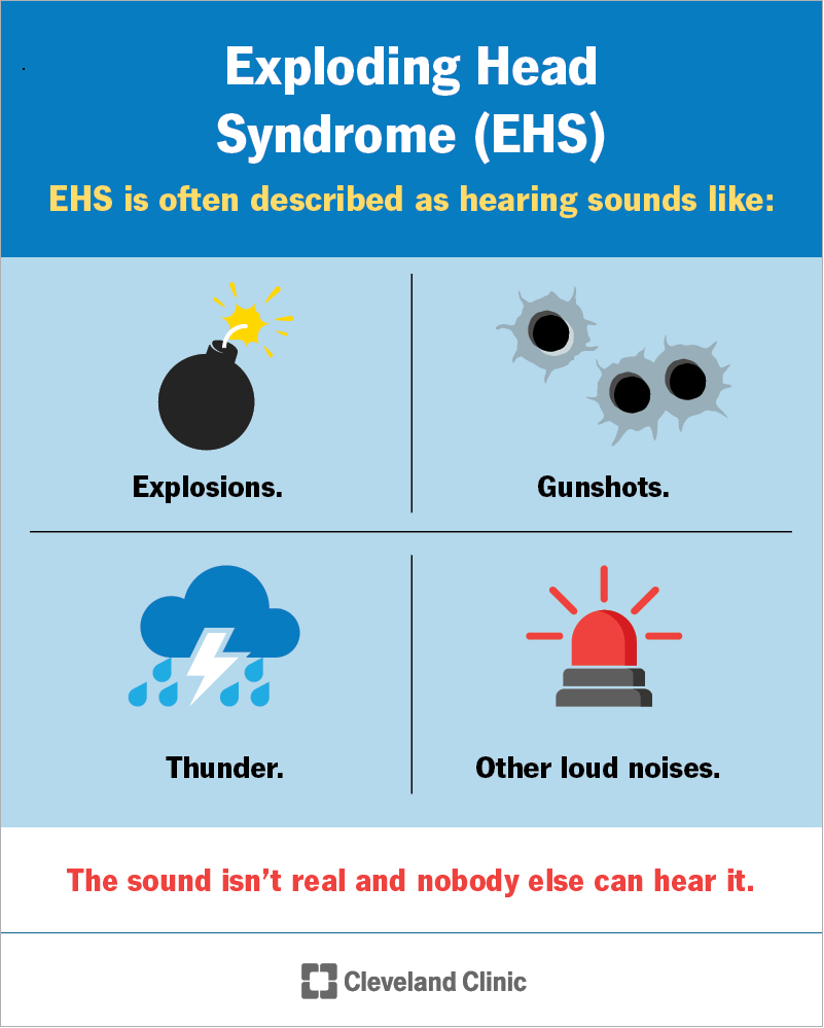

While not directly caused by external alarm sounds, certain sleep-related phenomena involving the perception of sudden, loud noises offer insights into the brain's capacity for intense auditory experiences during vulnerable sleep-wake transitions. Exploding Head Syndrome (EHS) is a benign parasomnia characterized by the subjective sensation of a sudden, extremely loud noise—often described as an explosion, gunshot, thunder, or other cacophonous sound—occurring typically as an individual is falling asleep or waking up.25 These episodes lead to abrupt awakening and are often accompanied by a sense of fear, distress, and sometimes a flash of light, although crucially, they do not involve significant physical pain. The perceived sound is internally generated, lasting less than a second, but its impact can be profoundly frightening, with patients often fearing serious neurological events like a stroke or tumor.

The exact etiology of EHS remains unclear, with proposed hypotheses including aberrant attentional processing during sleep-wake transitions, dysfunction in brainstem neurons (possibly involving the reticular formation), or disruptions in serotonergic pathways.26 Although EHS is an internally generated auditory hallucination and alarm clock sounds are external stimuli, the subjective experience of EHS provides a valuable, albeit amplified, analogue for understanding the potential "panic trigger" nature of particularly jarring alarm clocks for susceptible individuals. Both phenomena involve sudden, loud, and distressing auditory events occurring during the vulnerable transitional states between sleep and wakefulness.

The brain, in these states, may be more prone to misinterpretation or heightened reactivity to auditory stimuli. The intense fear and distress reported by EHS patients 25, often stemming from the startling nature of the sound and uncertainty about its cause, parallel, in a more extreme form, the anxiety and panic-like feelings that some individuals report in response to very harsh alarm sounds.

Studying the neural and psychological mechanisms underlying EHS, such as potential dysfunctions in sensory processing or arousal systems during sleep transitions, could therefore offer indirect insights into the spectrum of auditory sensitivity and reactivity around sleep. It highlights that for some, the auditory assault of a harsh alarm might tap into similar pathways of distress and alarm that are pathologically activated in EHS, moving beyond simple annoyance to a more profound sense of being startled and overwhelmed.

The alarm clock, in its various guises, has a history stretching back millennia, evolving from rudimentary natural mechanisms to sophisticated electronic devices. Throughout this evolution, the design of its sound-producing elements has been shaped by available technology, societal needs, and prevailing design philosophies, often prioritizing functional arousal over the qualitative experience of waking.

The quest to measure time and mark its passage is ancient, with early civilizations like the Sumerians and Egyptians developing foundational time-measuring devices.27 Among the earliest known automated wake-up mechanisms were the water clocks, or klepsydras, of ancient Greece.

The Greek philosopher Plato, in the 4th century BCE, is credited with converting a water clock into a wake-up machine for his academy students. These devices operated on the principle of rising water levels triggering a sound. One of Plato's designs reportedly produced a whistling sound as water displacement forced air through an orifice, while another caused pebbles to fall and rattle onto a resonant surface when a receiving basin became full. Later, in the 3rd century BCE, the inventor Ctesibius of Alexandria refined the water clock, creating a system with an overflow valve that, as a lower tank filled and rose, would make "little noises, similar to a cuckoo clock".30

These early devices signify the first documented attempts at automated, sound-based waking. The sounds they produced were often incidental byproducts of their mechanical function—the gurgle of water, the clatter of pebbles, the sigh of escaping air—rather than sounds intentionally designed for specific acoustic properties or optimal arousal. The primary engineering challenge was to create any perceptible auditory event at a predetermined time, marking a shift from reliance on natural cues like sunrise or animal sounds.

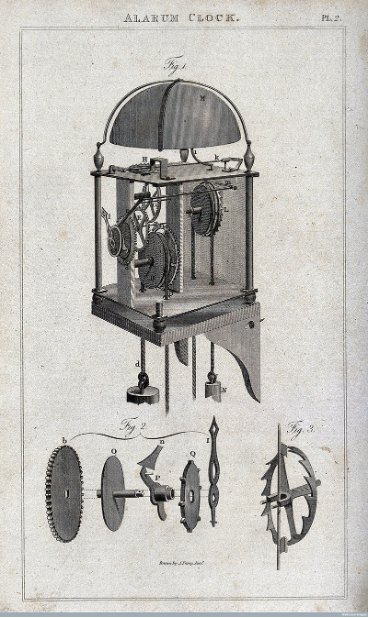

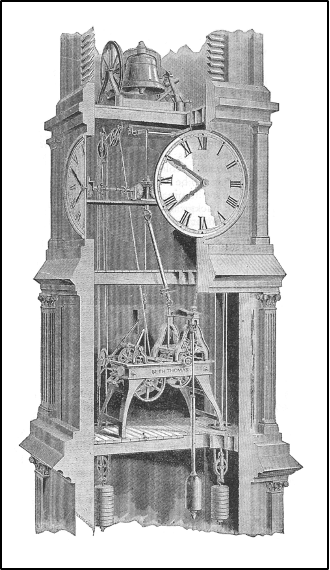

The advent of mechanical clocks in Europe, around the 14th century, brought with it the integration of more deliberate alarm functions. Dante Alighieri's "Divine Comedy," written around 1320, contains what is considered the first precise description of a clock movement equipped with an alarm mechanism. By the 15th century, user-settable mechanical alarm clocks existed in Europe, typically featuring a ring of holes in the clock dial into which a pin could be placed to designate the alarm time.31 An example of such an early device is the Gothic iron clock with an alarm, dating to circa 1580. The sound mechanism for these early mechanical alarms would have predominantly involved bells struck by hammers, a fundamental acoustic principle that would endure for centuries, establishing the bell as the archetypal alarm sound.

The 19th century's Industrial Revolution profoundly reshaped societal structures, work patterns, and the perception of time itself. The agrarian rhythms of seasonal tasks and irregular hours were supplanted by the rigid, clock-dictated schedules of factory work. In this new industrial landscape, punctuality transformed from a personal virtue into an economic necessity.27 This societal shift created a fertile ground for the development and proliferation of personal alarm clocks.

Several key inventions marked this era. In 1787, Levi Hutchins, an American clockmaker, created a personal mechanical alarm clock. However, his device was designed for his own use and could only ring at a fixed time of 4 a.m., the hour he wished to awaken. Its mechanism involved a pinion that, when tripped by the clock's hand, set a bell in motion, producing what Hutchins described as "sufficient noise to awaken me almost instantly".27 Hutchins notably never patented or mass-produced his invention, his motivation being personal discipline rather than commercial enterprise.29 A more pivotal development came in 1847 when French inventor Antoine Redier patented the first adjustable mechanical alarm clock, which bore a closer resemblance to the alarm clocks that would become commonplace. This adjustability was crucial for widespread adoption, allowing individuals to set their own waking times according to varied work shifts and personal needs.

The sound-producing mechanisms of these 18th and 19th-century mechanical alarm clocks typically consisted of one or two metal bells. A mainspring powered a gear train that, at the designated time, would rapidly move a hammer back and forth, striking the bell(s) repeatedly. In some designs, the metal back casing of the clock itself served as the resonant bell. Larger public clocks of the era, such as turret clocks in church towers, employed similar, albeit larger-scale, bell and hammer mechanisms to announce the hours.35 The sound quality of these alarms was characterized by its loudness and often strident nature; descriptions include "loud enough to wake the dead" 28 and "perturbin' sleep disturbin'".24 The primary design consideration was reliable, forceful arousal.

Industrialization not only spurred the invention but also enabled the mass production and affordability of alarm clocks.27 Initially, robust wooden clocks from workshops in regions like Germany's Black Forest provided a relatively inexpensive means of being reliably awakened. These were followed by industrially produced table clocks, often based on American "cottage clock" designs, which frequently incorporated alarm functions. By the late 1870s, mass-produced spring-driven alarm clocks became available in the United States for as little as $1.50.24

The mass adoption of these loud, mechanical alarm clocks was more than a mere technological trend; it was a critical enabler of the synchronized labor force demanded by industrial capitalism. Factory bells had initially served to impose temporal discipline on communities 32, but the personal alarm clock shifted this responsibility to the individual worker. The alarm's primary function became one of social and economic regulation, prioritizing punctuality over the individual's subjective waking experience. The sounds needed to be unequivocally loud and effective to rouse workers from sleep, regardless of sleep depth or personal comfort. Thus, the alarm clock evolved into an instrument of temporal discipline, aligning individual sleep-wake cycles with the relentless demands of industrial production and effectively standardizing the start of the workday for vast segments of the population. This historical context reveals an early precedent for prioritizing the "effectiveness" of waking over the "experience" of waking.

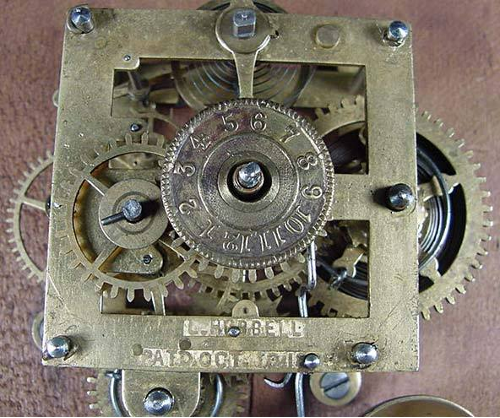

The 20th century witnessed the electrification of timekeeping and, consequently, alarm mechanisms. Early electric alarms often mimicked the noise reproduction principles of existing electrical devices like the electric doorbell, invented by Joseph Henry in 1831, which used an electromagnet to create a ringing sound.36 Electronically operated bell-type alarm clocks employed an electromagnetic circuit and an armature to repeatedly strike a bell.34 Even with the advent of transistor-based, solid-state alarm clocks in the 1960s, the sounds produced remained largely in the realm of "obnoxious" buzzing.

A notable early deviation from purely auditory alarms was the Westclox "Moonbeam" clock, first released in 1948. This innovative device initially attempted to wake the user with a bright, flashing light. If the light stimulus failed to rouse the sleeper after approximately 10 minutes, the clock would then resort to a loud buzzing sound. The Moonbeam represented an early, albeit uncommon, foray into multi-modal waking strategies.

The 1970s marked a significant turning point with the convergence of two key technologies: the piezoelectric transducer and the integrated circuit (IC). Piezoelectric buzzers offered a compact, inexpensive, and easily implementable way to generate sound. Critically, these transducers could be pulsed with short-duration spikes of electrical current to produce "ragged wave shapes." This acoustic characteristic, while potentially unpleasant, was considered highly "arresting" and therefore effective for an alarm, as articulated in a 1966 patent by Bronson M. Potter.36

Simultaneously, integrated circuits began to serve as the "brains" of low-cost consumer electronics. Companies like National Semiconductor developed chips (e.g., the MM5316) that consolidated all the necessary logic for clock and timer functions onto a single piece of silicon, dramatically reducing manufacturing costs and simplifying the production of digital alarm clocks. While early ICs like the MM5316 required an external sound generator (such as the piezoelectric transducer), later models (e.g., MM5382, MM5383 by 1977) incorporated tone-generation capabilities directly, often designed to produce sounds in the 400 Hz to 2000 Hz range, gated on and off at a rate of about 2 Hz. This technological pairing was instrumental in the proliferation of the ubiquitous, repetitive "beep beep beep" sound that became synonymous with digital alarm clocks—a sound chosen for its practicality, low cost, loudness, and difficulty to ignore.37

Alongside these developments, radio alarm clocks also emerged. The first to be mass-produced was the Musalarm 8H59 by Telechron, based on a 1946 patent by Francesco Collura, which combined a radio receiver with a timer mechanism, allowing users to wake to radio broadcasts.27

The dominance of harsh electronic beeps and buzzes in this era can be largely attributed to a path dependency created by early technological choices that favored low-cost, easily manufacturable components. The primary objective was effective waking at minimal production cost. The "arresting" quality of these sounds was perceived as a feature, not a flaw.36 Manufacturers, driven by the economics of mass production, widely adopted these cheap and "good enough" sound solutions.37 This established a de facto standard for alarm sounds, to which consumers became accustomed, even if the sounds themselves were disliked. Because these sounds fulfilled the basic function of waking people and were inexpensive to produce, there was little immediate economic incentive for manufacturers to invest in more complex and potentially costlier sound generation technologies that might offer a superior waking experience. This resulted in a prolonged period of stagnation in alarm sound design, where sounds were selected primarily for their manufacturability and their capacity to startle, rather than for their psychoacoustic impact on the user.

The enduring presence of jarring alarm sounds well into the late 20th and early 21st centuries was not accidental but rather a consequence of deliberate design philosophies, technological constraints, and economic considerations. The prevailing design philosophy, particularly in the era of early electronic and digital alarms, often prioritized the creation of "arresting tones". The explicit goal was to produce a sound that was maximally effective at capturing attention and rousing a sleeper, with the pleasantness of the auditory experience being a secondary, if considered at all, concern. As noted in patent literature, a "ragged wave shape" was deemed more "arresting," indicating an intentional pursuit of acoustically harsh characteristics.36

Cost-effectiveness and simplicity of manufacturing were also powerful drivers. The electronic circuitry required to produce a harsh beeping sound—essentially by rapidly turning a voltage fully on and off to a piezoelectric buzzer—was inexpensive and straightforward to implement. Generating more complex, potentially more pleasant-sounding tones would have required more sophisticated circuitry and thus incurred higher production costs.37 Given that the simpler, harsher sounds were effective at waking people and had become widely associated with the very concept of an alarm, manufacturers had little incentive to deviate from this proven and economical formula.

The introduction and widespread adoption of the snooze button can also be seen as a tacit acknowledgment of the unpleasantness of the primary alarm sound and the common human desire to delay the abrupt transition to full wakefulness.14 Interestingly, the common 9-minute snooze interval is thought to have originated from the mechanical gear limitations of early clock designs, a standard that was simply carried over into digital clocks due to user familiarity.

This historical trajectory of alarm clock sound design reveals a persistent dichotomy between "design for waking" and "design for well-being." From the earliest water clocks, where the challenge was to create any reliable sound at a specified time 27, through the Industrial Revolution, which amplified the need for loud, certain arousal to ensure a punctual workforce 32, to the electronic age, where cheap components enabled the mass production of "arresting" beeps and buzzes, the functional imperative of rousing a sleeper consistently overshadowed considerations of the qualitative experience and psycho-physiological impact of that awakening.

The alarm clock was primarily conceived and developed as a utilitarian "wake-up tool." Its potential to act as a "panic trigger" or a significant source of daily stress was an overlooked or, more likely, accepted side effect of its primary function, a compromise made in favor of efficacy and economy. It is only with more recent, wellness-focused design approaches, informed by a deeper understanding of sleep science and psychoacoustics, that a significant shift towards prioritizing the user's waking experience has begun to emerge.

To provide a clearer overview of this evolution, Table 1 summarizes key innovations:

Table 1: Timeline of Key Innovations in Alarm Clock Design and Sound Mechanisms

The alarm clock is more than a mere timekeeping device; it is deeply embedded in the fabric of modern life, its use shaped by societal norms, individual psychology, and cultural contexts. This section explores these dimensions, examining how the social construction of punctuality fuels alarm reliance, why individuals often persist with harsh alarms despite their drawbacks, and how alarm preferences and waking rituals can vary across cultures and demographics.

The intense societal emphasis on punctuality is a relatively modern construct, largely forged in the crucible of the Industrial Revolution. Prior to this era, daily life for many was dictated by natural rhythms—sunrise, sunset, the crowing of roosters.33 Industrialization, however, brought with it the factory system, demanding that large numbers of people work in synchronized shifts, adhering to strict timetables.27 As succinctly put, "Work! School! Meals! Appointments! Modern life demanded that everyone be on time!".24 This shift transformed punctuality from a desirable trait into a fundamental requirement for participation in economic and social life.

The alarm clock became a key instrument in this temporal reordering. Initially, factory bells and public clocks served to regulate collective schedules.32 However, with the advent of affordable personal alarm clocks, the responsibility for adhering to these schedules was increasingly individualized.24 Punctuality became an internalized discipline, a marker of reliability and efficiency.32 This reliance on alarms is not merely a matter of convenience; it is deeply intertwined with the need to navigate a world structured by precise timing. The pressure to be "on time" is a powerful social norm, and the alarm clock is the primary tool most people use to meet this pervasive expectation. Indeed, research suggests that subjective norms—the perceived social pressures to perform or not perform a behavior—can contribute to feelings of annoyance associated with waking up to an alarm, potentially because the alarm symbolizes the impending demands of these societal schedules.17

The alarm clock functions as an externalized conscience, enforcing societal time norms. Its sound triggers not just irritation from abrupt waking, but also stress from what it represents: the start of obligations, the pressure to conform, and the shift from private rest to public responsibility.

Despite the known downsides of jarring alarm sounds, many individuals continue to use them. This persistence can be attributed to a complex interplay of psychological factors, learned behaviors, and perceived necessities. A primary reason is the perceived effectiveness of harsh alarms. Individuals who consider themselves deep sleepers, or who have an overriding fear of oversleeping and facing the consequences (e.g., being late for work, missing important appointments), may believe that only a loud, grating sound can reliably rouse them.18 For these users, the anxiety associated with not waking up outweighs the discomfort of an unpleasant awakening. This "fear of not waking" often becomes a stronger motivator in alarm selection and usage patterns than the desire for a gentle or stress-free transition to wakefulness. Consequently, they may consciously choose alarms that are maximally effective in their startling capacity, even if such sounds induce stress.

Habituation and neural adaptation also play a significant role. The human brain is adept at filtering out repeated, familiar stimuli. Over time, neurons can grow accustomed to a specific alarm sound, leading to a phenomenon where the alarm loses its effectiveness in waking the individual.14 This passive habituation might compel users to seek out progressively louder or more jarring sounds, or to set multiple alarms in an attempt to counteract this adaptation. The widespread use of the snooze button is another indicator of this dynamic, reflecting both a desire to delay the unpleasantness of the primary alarm and a potential dissatisfaction with the abruptness of the waking experience. For some, particularly "night owls" or those with inconsistent sleep schedules, hitting the snooze button becomes a deeply ingrained habit.18

Furthermore, negative psychological associations can develop. If an alarm clock is consistently linked with a stressful morning rush or an unpleasant jolt from sleep, individuals may subconsciously begin to dread the sound, fostering a negative morning mindset even before the alarm activates. Another contributing factor may be a lack of awareness or accessibility regarding less stressful alternatives. While gentler alarm options exist, users may not know about them, or they might perceive them as being less effective, more expensive, or requiring more effort to set up compared to the default beeps on their phone or old clock.23 Some users, particularly those who find it very difficult to wake, may even opt for "hard alarms" that require performing cognitive or physical tasks (like solving puzzles or taking a specific photo) to deactivate them; these task-based alarms, while effective for ensuring wakefulness, have been linked to increased feelings of nervousness upon waking.17

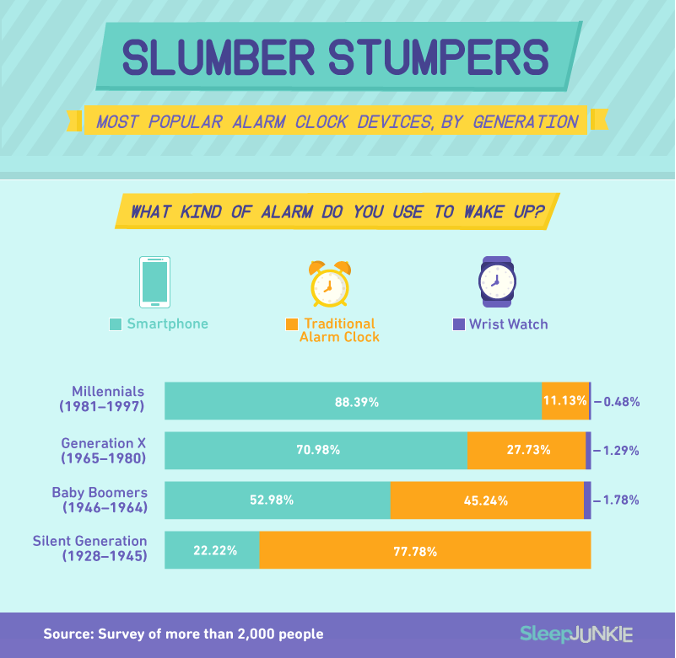

Alarm clock usage and waking habits are not uniform globally but exhibit variations influenced by demographics, cultural norms, and even geographical location. One of the most significant demographic shifts has been the ascendancy of the smartphone as the primary alarm device. Younger generations, including Millennials and Gen Xers, overwhelmingly rely on their smartphones, with nearly 90% of those 35 or younger and over 70% of Gen Xers using them for this purpose. In contrast, a significant majority of the Silent Generation (almost 78%) still prefer traditional, stand-alone alarm clocks. Baby Boomers fall in between, with a slight majority (around 53%) having migrated to smartphone alarms.38

Even within smartphone users, preferences for default alarm tones can show subtle demographic differences. For instance, one survey indicated that women were more likely to rank Samsung's "Morning Flower" as their go-to alarm sound, while men tended to prefer Apple's "Radar" tone, although choosing custom sounds was also popular across genders.38

Cross-cultural studies reveal more pronounced differences in morning experiences and potentially related alarm usage. A study comparing users in the United States and South Korea found that US participants reported feeling significantly less tired in the morning but were more likely to feel nervous compared to their South Korean counterparts. Conversely, Korean users had lower odds of feeling hopeful upon waking. Notably, South Korean participants were more likely to report experiencing no specific emotions in the morning, a finding that researchers suggested might be linked to cultural differences in emotional expression, with individuals in Western cultures often being more overtly expressive than those in some Eastern cultures.17 These findings underscore that cultural factors can significantly shape morning emotions, which may, in turn, influence alarm preferences and waking behaviors.

Chronotype—an individual's natural propensity to be a "morning type" or "evening type"—also shows international variation. For example, a study involving medical students found that Malaysian students tended to wake earlier and identify as morning types more frequently than students in the US or UAE. Other research has suggested that populations living closer to the equator may perceive themselves as more morning-oriented, possibly due to more consistent daylight patterns.39

Historically, before the widespread availability of personal alarm clocks, waking rituals varied greatly. People relied on natural environmental cues like sunrise or the crowing of roosters, communal signals such as church bells, or even professional "knocker-uppers" who were hired to tap on windows in industrial towns in Britain to wake workers for their shifts.33 Some societies, like those in medieval Europe, are believed to have practiced biphasic sleep, with two distinct sleep periods during the night.40

These variations suggest the existence of "cultural scripts" for morning affect and interaction with waking technologies. Differences in cultural values (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism), emotional display rules, societal expectations around productivity, and even environmental factors like latitude and its effect on sunrise times, likely influence not only the types of alarms chosen but also the "acceptable" or "expected" emotional response to waking. For instance, in a culture that emphasizes stoicism, individuals might be less inclined to report negative feelings from an alarm, even if a physiological stress response is present. Conversely, cultures that highly value an energetic start to the day might have different expectations for morning mood, influencing choices towards alarms perceived as "energizing," regardless of their acoustic harshness. This implies that a universally "optimal" alarm sound or waking experience may not exist, and effective design may need to consider these deeply ingrained cultural scripts.

The proliferation of smartphones has fundamentally altered the landscape of alarm clock usage. With powerful, built-in, and highly customizable alarm functionalities, smartphones have significantly diminished the demand for traditional, standalone alarm clock devices, particularly among younger demographics who have grown up with this technology.38 The convenience of having an alarm integrated into a device that is already an indispensable part of daily life, coupled with the ability to choose from a vast library of sounds or use personal music tracks, has made the smartphone the default alarm for a large segment of the population.42

This shift has had a clear impact on the electronic alarm clock market, which faces considerable competition from the alarm features inherent in nearly every smartphone. However, this challenge has also served as a catalyst for innovation within the dedicated alarm clock sector. Manufacturers are increasingly focusing on developing "smart" alarm clocks that offer features beyond simple timekeeping and basic alarms, aiming to provide value that a standard smartphone app might not. These features often include integration with smart home ecosystems, voice assistant compatibility, wireless phone charging, ambient lighting, and advanced sleep and wellness functions.42

This situation presents a paradox: while smartphones offer unprecedented potential for users to select personalized and potentially healthier alarm sounds (such as melodic music or natural soundscapes, which research suggests can be beneficial), this potential often appears to be underutilized. Many users tend to stick with the default alarm tones provided by their phone manufacturers (e.g., Apple's "Radar" or Samsung's "Morning Flower" remain highly popular choices 38), which can still be quite abrupt or acoustically annoying, as evidenced by user complaints about certain default sounds.23

Furthermore, the very accessibility and convenience of the smartphone can make behaviors like repeatedly hitting the snooze button effortless, potentially leading to fragmented sleep and increased morning grogginess.18 Thus, while the technology for a better auditory waking experience is readily available in most people's pockets, a combination of user habits, the nature of default settings, and perhaps a lack of awareness or motivation may prevent the widespread adoption of more psychologically sound alarm choices that these powerful devices could easily support. This points to a significant opportunity for improvement in default sound design by phone manufacturers and a need for greater user education on the impact of their alarm sound choices.

In response to the growing awareness of the negative impacts of traditional alarm clocks, recent years have seen a surge in innovative approaches to waking technology. These newer methods aim to prioritize user well-being by leveraging scientific understanding of sound perception, light therapy, and sleep physiology. This section examines these current trends, from psychoacoustically informed sound design to sophisticated multimodal systems, and analyzes their market adoption.

A significant area of innovation lies in redesigning the alarm sound itself. Research increasingly supports the idea that the acoustic characteristics of an alarm can profoundly influence the waking experience.

These findings suggest a "sweet spot" hypothesis for alarm sound design. The challenge is to create sounds that are sufficiently arousing to overcome sleep inertia and reliably wake the user, yet simultaneously possess acoustic characteristics that promote positive valence and minimize physiological and psychological stress. This likely involves a nuanced approach, moving beyond simple loudness to consider melodic contours, moderate and gradually increasing tempos, and timbres that avoid excessive harshness, abruptness, or dominant high-frequency energy. The goal is not just to make alarms "softer," which might compromise their effectiveness for some, but to make them "smarter" by carefully engineering their acoustic structure based on psychoacoustic principles. Table 2 provides a summary of how key acoustic properties can influence affective responses.

Table 2: Acoustic Properties and Their Influence on Affective Response to Sound

Sunrise alarm clocks, also known as dawn simulators, represent a significant departure from purely auditory waking methods. These devices aim to replicate a natural sunrise by gradually increasing the intensity of light in the bedroom over a set period, typically ranging from 15 to 40 minutes, before the user's desired wake-up time.9 The underlying principle is to engage the body's natural circadian rhythm. Morning light is a powerful zeitgeber (time cue) that signals the brain to suppress the production of melatonin (a sleep-promoting hormone) and gradually increase the production of cortisol (a hormone that, in this context, prepares the body for alertness and activity).8

The reported benefits of using sunrise simulators are numerous:

A study investigating a multimodal intervention that combined light, sound, and ambient temperature changes found that while the overall impact on sleep inertia was limited, the participant's chronotype and, crucially, the length of the lighting exposure during the intervention mornings did influence the outcomes. For instance, moderate evening types who received a shorter lighting duration (≤ 15 minutes) experienced more lapses on a psychomotor vigilance test (PVT) compared to their control condition. In contrast, intermediate chronotypes showed improved response speed and fewer lapses with the intervention. When the lighting duration was longer (> 15 minutes), evening types showed benefits such as fewer false alarms on the PVT and lower negative affect. These findings suggest that the duration of light exposure is a critical factor in the efficacy of such systems, and that optimal durations might vary depending on an individual's chronotype. The study authors primarily attributed the observed differences in outcomes to the lighting component of the multimodal alarm.53

The primary benefit of sunrise simulators may thus extend beyond providing a subjectively gentler wake-up stimulus. Their more profound and potentially more significant impact could lie in their capacity to consistently entrain and stabilize the user's circadian rhythm over time. By providing a reliable daily light cue that mimics a natural dawn, these devices can help reinforce the body's intrinsic sleep-wake cycle. A well-regulated circadian rhythm naturally leads to more robust internal cues for waking, potentially diminishing the long-term reliance on any form of external alarm. This shifts the paradigm from forceful awakening to supportive biological entrainment, fostering a more natural and sustainable waking process. Market data reflects a growing consumer interest in this technology, with sales of alarm clocks featuring daylight simulation increasing significantly in recent years.54

The convergence of wearable technology, sophisticated sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI) is paving the way for highly personalized and multimodal waking systems. A key feature of many "smart" alarms and wearable devices (like smartwatches and fitness trackers) is sleep cycle tracking. These systems aim to monitor the user's sleep stages (light, deep, REM) and intelligently time the alarm to coincide with a period of lighter sleep, theoretically minimizing sleep inertia and making the awakening process feel less jarring and more natural.13

Vibrotactile alarms, often integrated into wearables, offer a silent alternative or supplement to auditory alarms. Tactile stimulation, such as vibration on the wrist, can be an effective means of arousal and is sometimes associated with positive valence, potentially enhancing the pleasantness of waking, especially if triggered during shallow sleep stages. Research into different vibrotactile modulation techniques (e.g., simultaneous, continuous, or successive stimulation) suggests that continuous modulation may be highly perceivable and linked to positive attention. While effective in waking healthy individuals, their efficacy might be reduced in certain patient populations.55

AI-powered sleep monitors are emerging that go beyond simple sleep tracking to analyze individual sleep patterns in depth and provide personalized waking strategies.13 These might involve adjusting alarm timing, sound type, or light exposure based on the previous night's sleep quality or long-term sleep trends. Modern smart alarm clocks are also increasingly multifunctional, incorporating features like wireless device charging, Bluetooth speakers for streaming audio, voice assistant integration (e.g., Alexa, Google Assistant), ambient mood lighting, and connectivity with broader smart home ecosystems.42 This allows for a more integrated morning experience, where the alarm might also trigger other smart home devices like lights or coffee makers.

The market for wellness-centric alarm clocks is also expanding, with devices offering features designed to promote relaxation and better sleep hygiene, such as guided breathing exercises, white noise generation, nature soundscapes for sleep, and even biofeedback mechanisms.42 Multimodal interventions, which combine elements like light, sound, and sometimes even temperature changes, are being explored, though research indicates that the interactions between these modalities can be complex. As previously noted, a study on such a system found that lighting duration and user chronotype were significant factors influencing outcomes, more so than the combination of stimuli itself in some respects.53

This trend towards data-driven, personalized awakenings holds considerable promise. Smart and multimodal systems, by leveraging sleep tracking and AI, could theoretically tailor the waking experience to an individual's unique physiological state, sleep cycles, and chronotype. However, the ultimate effectiveness of these sophisticated systems hinges on several factors. Accurate sleep stage detection by consumer-grade sensors remains a challenge. The sophistication of the algorithms used to interpret sleep data and trigger alarms is crucial. User willingness to engage with, trust, and potentially share data with these technologies is also a key consideration, alongside inherent privacy concerns associated with the collection of sensitive biometric data. If these systems are not sufficiently accurate, adaptable, or transparent, they risk offering a false sense of optimization or could even introduce new sources of anxiety if they consistently fail to deliver on their promise of a "perfect" or significantly improved awakening. The potential is vast, but so are the challenges in realizing truly effective and reliable hyper-personalized waking solutions.

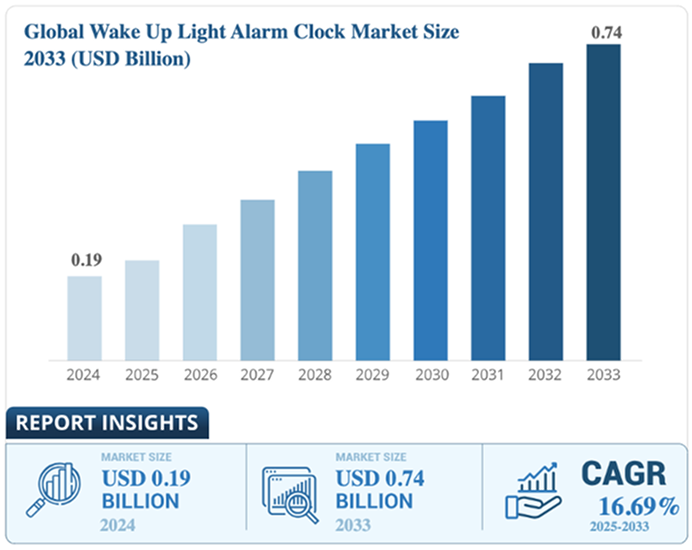

The alarm clock market is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by technological advancements and evolving consumer preferences that increasingly prioritize wellness and smart home integration. While traditional basic alarm clocks face pressure from the ubiquity of smartphone alarms, the market for more advanced electronic alarm clocks is showing robust growth, particularly for models offering features beyond simple time-telling.

Smart and multifunctional alarm clocks are in high demand. Consumers are increasingly seeking devices that provide more than just a wake-up call, with features like wireless phone charging, integrated Bluetooth speakers, FM radio, USB charging ports, voice assistant compatibility (Alexa, Google Assistant), and ambient lighting being key drivers of adoption.42 Globally, smart alarm clocks equipped with Bluetooth, FM radio, and USB charging now constitute 39% of all units sold.54

Daylight simulation or sunrise alarm clocks are particularly popular. In 2023, 52% of North American users expressed a preference for alarms with these features. Worldwide, sales of these devices reached over 12.5 million units in 2023, marking a substantial 41% increase from 2020.54 This indicates a strong consumer interest in gentler, more natural waking methods.

The wellness-centric segment of the alarm clock market is also experiencing significant expansion. Alarms incorporating features such as gradual light-based wakeups, white noise generation, guided breathing exercises, and even meditation guides saw a 37% growth in global sales in 2023. Smart clocks that include sleep tracking capabilities and ambient mood lighting saw a 29% increase in adoption in developed countries during the same period.

In terms of display technology, LED-based alarm clocks currently dominate the market, accounting for approximately 58% of global unit sales in 2023. Their popularity is attributed to superior visibility, especially in low-light conditions, and features like automatic brightness adjustment. LCD-based models make up the remaining 42% of sales, valued for their lightweight construction, compact designs, and affordability.54

The impact of smartphones is twofold: while their built-in alarm functions challenge the market for basic traditional clocks, they also fuel innovation in the smart alarm clock category. Consumers accustomed to the connectivity and features of their smartphones are now seeking similar integration in their dedicated alarm devices, particularly those that can seamlessly connect with their smart home ecosystems.42 E-commerce platforms have become the primary sales channel, accounting for 61% of global alarm clock sales in 2023.54 Aesthetic considerations also play a role, with a trend towards compact, minimalist designs in neutral tones, and an increasing interest in alarm clocks made from eco-friendly materials like bamboo.54

These market dynamics suggest an evolution of the alarm clock's role. It is transforming from a standalone, single-function device into a potential component of a broader "sleep ecosystem" focused on holistic sleep health and morning wellness. This shift positions the alarm clock, often a consistent bedside fixture, as a potential data collection point (for sleep patterns), an intervention tool (providing light therapy, soundscapes, or guided relaxation), and an interface for interacting with other smart devices that contribute to a healthy sleep environment (e.g., smart thermostats, automated blinds).

This evolution presents significant opportunities for manufacturers to innovate but also brings challenges related to data integration, user interface design, ensuring genuine evidence-based wellness benefits, and addressing data privacy.

Table 3: Market Adoption and Consumer Preferences for Modern Alarm Technologies

To further advance the design of waking technologies towards enhanced user well-being, systematic comparative research is essential. Understanding the nuanced effects of different alarm modalities requires robust methodologies and a clear identification of key areas for investigation.

A comprehensive assessment of how different alarm technologies impact individuals necessitates a multi-faceted approach, triangulating data from various sources to capture the complexity of the waking experience.

Relying on a single type of measure can be misleading; for example, an individual might exhibit clear physiological signs of stress but report feeling "fine" due to subjective biases or habituation, or vice-versa. Therefore, future comparative studies should strive for this multi-method triangulation to develop a holistic understanding of how different alarm technologies affect individuals across physiological, cognitive, and affective domains.

Building on existing knowledge, several key areas warrant focused comparative investigation:

A critical factor that often moderates the effectiveness of waking interventions is individual chronotype (an individual's innate preference for morning or evening activity). The study on multimodal interventions highlighted that chronotype (moderate evening vs. intermediate types) interacted significantly with the duration of light exposure to affect sleep inertia symptoms. "Night owls," whose circadian rhythms are naturally phase-delayed, often find early mornings particularly challenging.18

A "one-size-fits-all" alarm, even an innovative one, may not be equally beneficial for "larks" and "owls." For example, evening types might require longer or more intense light exposure, or perhaps different sound profiles, to achieve an optimal awakening. Therefore, future comparative studies must not only compare Alarm A versus Alarm B across a general population sample but should also stratify participants by chronotype or use chronotype as a covariate in their analyses. This could lead to the development of chronotype-specific alarm settings or even entirely different alarm systems tailored to an individual's unique biological predispositions, moving towards truly personalized waking solutions.

Despite recent advancements, several research gaps and opportunities for human-centered design in waking technologies remain:

One particularly promising, yet largely untapped, area for future research and design innovation lies in the concept of "pre-wake" auditory stimuli. This idea draws inspiration from the phenomenon of prepulse inhibition (PPI), where a non-startling sensory stimulus presented shortly before an intense, startle-inducing stimulus can significantly reduce the magnitude of the startle response.21 Most conventional alarms deliver an abrupt, high-intensity sound without any preceding warning, thereby maximizing the startle effect and the associated stress. Sunrise simulators already employ a form of "pre-wake" stimulus using gradually increasing light.9

A similar principle could be applied to sound. Imagine an alarm system that, for several minutes before the primary wake-up sound, introduces very low-intensity, non-jarring auditory cues. These could be slowly evolving natural soundscapes, simple, gentle melodic fragments, or even gradually increasing white or pink noise. This "auditory dawn" could serve multiple purposes: gently nudging the brain towards lighter sleep stages, subtly lowering the arousal threshold needed for the final wake-up call, and potentially engaging PPI-like mechanisms to dampen the physiological shock and perceived unpleasantness of the main alarm, even if that main alarm needs to be reasonably salient to ensure waking.

Comparative studies could systematically test various pre-wake auditory protocols (differing in duration, intensity progression, and sound type) against standard alarms and sunrise simulators to determine if this sequential approach can further mitigate morning stress and sleep inertia. This would represent a shift from merely changing the characteristics of the main alarm sound to redesigning the entire auditory waking sequence for a more neurologically considerate transition from sleep to wakefulness.

Table 4: Comparative Physiological and Psychological Effects of Different Waking Methods

The daily act of waking, so fundamental to human existence, has been profoundly shaped by the alarm clock. This report has traced its journey from a simple tool for punctuality to a complex psycho-technological interface, revealing that the sounds designed to rouse us often trigger a cascade of unintended negative consequences.

Traditional alarm clocks, with their characteristically abrupt and harsh auditory signals, can act as significant morning stressors, initiating acute physiological stress responses including elevated heart rate, increased blood pressure, and surges in stress hormones like cortisol. These awakenings frequently exacerbate sleep inertia, leading to prolonged periods of grogginess and impaired cognitive function. The emotional toll is also considerable, with many users experiencing annoyance, anxiety, and a generally negative start to their day, sometimes developing a conditioned aversion to the alarm itself.

The historical trajectory of alarm clock design, particularly its sound mechanisms, reveals a long-standing prioritization of functional efficacy—the certainty of waking—over the qualitative experience of that awakening. From the loud mechanical bells necessitated by the Industrial Revolution's demand for a synchronized workforce to the cost-effective piezoelectric buzzers and beeps of the early electronic era, the primary goal was to create an "arresting" stimulus. Societal pressures for punctuality further reinforced reliance on these often-unpleasant devices, with cultural and demographic factors subtly shaping alarm preferences and waking rituals.

However, a paradigm shift is underway. Fueled by a deeper understanding of sleep science, psychoacoustics, and chronobiology, coupled with advancements in sensor technology and AI, a new generation of waking technologies is emerging. Melodic alarms and natural soundscapes have demonstrated potential in reducing sleep inertia and mitigating stress. Sunrise simulators, by mimicking natural dawn, offer a gentler, light-based approach that can improve mood, reduce grogginess, and help regulate circadian rhythms. Smart and multimodal systems, including wearables, are striving for personalized waking strategies by tracking sleep cycles and combining various sensory inputs. Market trends reflect a growing consumer appetite for these wellness-centric features, indicating a collective desire for a less traumatic morning ritual.

The path forward requires a concerted effort to move definitively from a philosophy of "design for waking" to one of "design for well-being." This involves several key recommendations:

For Users:

For Designers and Manufacturers:

For Researchers:

The morning alarm need not be a daily antagonist. By integrating scientific knowledge with human-centered design principles, it is possible to transform this ubiquitous device. The goal is to redesign the morning ritual, shifting the wake-up call from a source of panic and stress to a peaceful and positive commencement of the day, thereby contributing to enhanced productivity, improved mood, and overall greater well-being.

Alarm clocks are essential tools of modern life, yet for many, they trigger stress rather than support a smooth transition into wakefulness. This in-depth research report explores the overlooked relationship between alarm sound design and the body’s morning stress response, tracing the evolution of alarms and the cultural habits that shaped them. It examines how sonic characteristics directly affect cognition, mood, and physiological arousal upon waking.

For the last decade, the marketing mandate has been simple: Speed. Identify the trend, mimic the trend, monetize the trend. But the machinery of cool has broken down. The trend cycle, which once moved on a breathable 20-year loop, has collapsed into a hyper-accelerated blur of micro-aesthetics that rise and die in weeks. It is time to stop chasing. It is time to build Cultural Antibodies.

Hermès commissioned nearly 80 creatives - illustrators, animators, artists, to generate social-content aligned with “Drawn to Craft.” That means instead of traditional product shots or celebrity ads, you get a mosaic of artistic interpretations keyed to craft, heritage and creative vision.

Drop us a note and we’ll

schedule a free consultation.