Film photography is selling out. Brands are reaching for handwritten fonts, illustrations and fine art style even in B2B (see Intercom), deliberately uneven and imperfect. Flash photography, once dismissed as unrefined, is now the aesthetic of choice on fashion runways. Stripe Press - a fintech company better known for code than for culture - prints cloth-bound books. The signals are scattered but consistent: we are circling back to what feels slower, tactile, and finite.

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s a cultural correction.

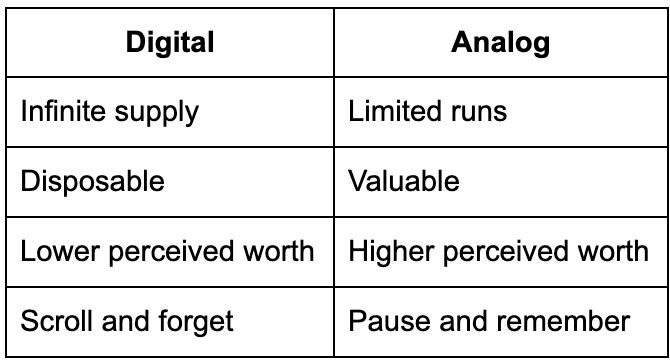

Digital has taught us to live in endlessness. Updates slip into our devices overnight, apps appear and vanish within months, feeds scroll without end. It is a world of abundance, and yet that very abundance makes each piece of content feel weightless.

Analog, by contrast, imposes limits. A roll of film gives you thirty-six frames. A limited print run means you might miss your chance if you hesitate. A workshop offers only as many seats as the room will hold. Scarcity slows us down. It forces choices. And in those choices, meaning takes root.

To think of analog only as film cameras or vinyl records is to miss the breadth of what is happening. Analog today is any act - visual, material, or experiential that introduces texture, friction, or ritual into the way we encounter a brand or a piece of culture.

It is the decision to use handwritten type in an identity system, not for nostalgia but to remind us that a hand once pressed pen to paper.

It is the use of papercraft, charcoal, or stop-motion animation, where the trace of the tool is part of the work itself.

It is the workshop that asks you to stitch your own pair of sneakers, or the coffee roaster who invites you to learn slow brewing as ritual rather than transaction.

These gestures matter not because they are old-fashioned, but because they feel human.

The list of examples grows longer every year. Byredo chooses to shoot on film, where grain is not a flaw but intimacy. Leica and Fujifilm cannot produce film cameras fast enough to meet demand, even though phones technically take “better” pictures. Flash photography, with all its harshness, dominates fashion shows precisely because it is immediate and unfiltered.

Stripe Press continues to bind its books in cloth, not because it cannot produce PDFs, but because a hardcover announces seriousness and longevity. The Economist still prints special subscriber editions, knowing that scarcity deepens attachment. Beauty and fashion brands invest in stores, labs, and pop-ups not simply to sell but to let people touch, smell, and participate.

Taken together, these are not eccentricities. They are signals of fatigue with digital abundance, and of hunger for something tangible to hold onto.

One might ask: if AI can simulate handwriting, generate fake film grain, or mimic stop-motion, then why bother with analog at all?

The answer lies not in the outcome but in the process. Analog is less about how it looks, and more about how it feels to make and to experience.

Film forces you to think before you click. Handwriting suggests that someone took the time to inscribe a thought. Brewing coffee slowly engages all five senses. Printing a book makes you check and go over the content a million times because you cannot go back and edit what you published. A pop-up store that you step into, with its sounds, smells, and textures, becomes an embodied memory in a way no digital campaign can replicate.

AI can mimic the surface, but it cannot reproduce the ritual, the waiting, the weight of patience. Memory does not come from polish; it comes from process.

We tend to think of friction as something to be designed away. Yet humans need friction. It is how we remember.

Writing by hand improves retention. Readers trust information more when it is presented in physical books rather than on screens. Rituals - journaling, ceremonies, even the act of brewing coffee - carry meaning precisely because they are not instantaneous.

There is also a plain economic truth here. Digital is infinite, therefore cheap. Analog is finite, therefore valuable. (Think Hassleblad cameras.)

A workshop with limited seats, a book printed in a small run, a film camera with a finite roll - all these forms create scarcity, and scarcity creates desire. Brands that choose analog signal confidence: the willingness to invest resources in something that cannot be endlessly reproduced.

Scarcity is not a flaw. That is the point.

Analog reframes how we see a brand. It tells us:

We are deliberate.

We are not chasing speed.

We are building something larger than a campaign.

It is less about style than about stance. In a time defined by infinite content, analog gestures remind us of permanence, patience, and presence.

The irony of our age is that the smoother digital becomes, the more we long for imperfection. We are trained to recognize filters, to suspect polish, to doubt the simulated. What we seek instead are traces of the real: the uneven edge of a torn page, the grain in a photograph, the pause in a ritual.

Analog is not about going backward. It is not nostalgia for what was. It is a form of rebellion against what overwhelms us now. In a sea of infinite sameness, it creates an anchor -something to hold, something to remember, something to trust. It may well be the next code for what we call premium.

Alarm clocks are essential tools of modern life, yet for many, they trigger stress rather than support a smooth transition into wakefulness. This in-depth research report explores the overlooked relationship between alarm sound design and the body’s morning stress response, tracing the evolution of alarms and the cultural habits that shaped them. It examines how sonic characteristics directly affect cognition, mood, and physiological arousal upon waking.

For the last decade, the marketing mandate has been simple: Speed. Identify the trend, mimic the trend, monetize the trend. But the machinery of cool has broken down. The trend cycle, which once moved on a breathable 20-year loop, has collapsed into a hyper-accelerated blur of micro-aesthetics that rise and die in weeks. It is time to stop chasing. It is time to build Cultural Antibodies.

Hermès commissioned nearly 80 creatives - illustrators, animators, artists, to generate social-content aligned with “Drawn to Craft.” That means instead of traditional product shots or celebrity ads, you get a mosaic of artistic interpretations keyed to craft, heritage and creative vision.

Drop us a note and we’ll

schedule a free consultation.